on ADAPTING HAMLET

This has probably been the most complex and involved project I've ever completed, and I believe I will remember it as one of my favorite experiences at the Galloway School.

One of the biggest pedagogical benefits of multimodal projects like this one is that they invite students to engage with challenging tasks and texts from a place of security and strength by building on students' individual talents and expertise. Doing so helps students confidently take on responsibilities within such projects from a place of empowerment rather than anxiety. I witnessed these same patterns throughout the ADAPTING HAMLET project.

As we rounded the end of October 2015, it became clear that students in both AP Lit and British Literature could read Hamlet at the same time without too much manipulation of the schedule or of the deep reading groove that we had begun to establish together. Once I saw the possibility, I couldn't imagine not digging into Hamlet with all my students simultaneously. I quickly reimagined the major project for Hamlet not as 81 research-driven persuasive essays but as a DYNAMIC and collaborative multimodal project grounded in DARING and DELIBERATE interaction with a complex source text and striving for student DISCOVERY and empowerment.

daring"I learned how to be resilient, patient, and positive when faced with challenges outside our control and to stop attempting to control things I cannot control." |

Because I value both student independence and initiative, I actively cultivate spaces and opportunities for students to set the parameters of their engagement with our class texts and questions. To establish habits of deep inquiry with this daunting text together, we started Hamlet in each class by simply bringing life to Shakespeare's text. We assigned parts for each scene, and students read the text aloud. Once each student had taken a turn - an act of singular daring for a number of them - we began to recycle parts, and the students began to inhabit the different roles, trying out their voices, imagining their movements, empathizing with their plights, feeling their lived experiences.

During the read-along, I hoped to see some awe and wonder, flashes of understanding, lightbulb moments; I worried I would stare out at a sea of ambivalence. Reality was, unsurprisingly, somewhere in between. The increased interest in the text, the willingness that students brought with them to our readers' theater versions of the play, were indication enough for me to know that ADAPTING HAMLET would be a go. |

Though, in my excitement about the project, I wanted to simply tell each class to adapt one act of the play, I knew that sort of top-down directive, besides feeling wholly unnatural to me, would turn the burgeoning excitement and enthusiasm I saw into boredom at best and resentment at worst. Not interested in ennui, apathy, or mutiny, I opened the decision-making process up to them, trusting that the work we had done together establishing our habits of interaction with the text and one another would enable students to find an adaptation project they would undertake with both sophistication and enthusiasm.

|

Though we discussed the final shape of possible final artifacts, ranging from movie posters to short stories to poems to animated Hamlets, each class devoted multiple meetings to individual, small group, and whole class brainstorming and sharing sessions and ultimately decided that film was their medium of choice. Format and medium settled, each class drew at random one of the five acts of Hamlet and went about negotiating the terms and parameters of their class's adaptation.

|

deliberate"When people all want to accomplish the same goal, it does not take massive amounts of work. A project will exceed expectations if the people involved are truly passionate about the material." |

Through thinking routines like think-pair-share, students quickly recognized the substantial scope of the project they had chosen for themselves and began listing the many moving pieces and steps they might need to undertake to achieve their goals. These visible thinking sessions made it clear to everyone that this project would require careful planning, communication, and teamwork. To manage this monumental task, each class created a list of responsibilities they foresaw and divided these responsibilities up into teams, including writers, videographers, film editors, website editors, actors, tech crew, management, etc.

dynamic

Once teams were established, each student volunteered for the role and team they felt best equipped for and/or most excited to step into - that student's primary responsibility - as well as a secondary, stretch role and team that students would support first when not engaged in their primary role. Teams drafted contracts outlining expectations for individuals and their teams and responsibilities of each team to the whole class. Responsibilities assigned and agreed upon, the leadership teams planned a timeline with other team leaders, the writers and directors decided on their goals for their adaptation, the writer team adapted their class's act into a script, the directors and actors produced a filmed version of that act, each class workshopped the rough cuts of the scripts and film footage, and the web team and film editing team published their class's act digitally on a class-created and -curated website that contextualizes the class's adaptation.

"This project was my first experience being in charge of creative decisions, and it was a lot of responsibility. I learned how to create and execute a creative vision, and how to incorporate other people's ideas. I also learned a lot about navigating through challenges, like improvising when our venue is unavailable (not only once but twice). When we were no longer able to film in the theatre spaces, I refused to let the challenge stall our progress, especially considering the approaching deadline. I decided that our film's rhetoric relies mostly on cinematography, screenplay, and costumes rather than location, so we picked a place without missing a beat." discovery |

Students who had looked to the Hamlet unit in dread were excited about the opportunity to work to their strengths and were willing to reach beyond their comfort zone by taking on responsibilities they wouldn't have dreamed of embracing otherwise. Students with zero acting experience stepped in front of the camera as their secondary responsibility. Students who often were quiet found themselves as leaders within their teams.

ADAPTING HAMLET required students to embrace the vulnerability that goes hand in hand with increased responsibility. It also gave me many opportunities to model this mindset. Though my position as a teacher has never been at the front or center of the classroom, projects like this one challenge me to step even further to the side so that decisions about allocation of student talent and effort can be entirely student-driven. Given the ambitious scope of the project, its perceived "success" or "failure" would be impossible to hide. As a new member of the Galloway community, teaching at a new level, trying to cultivate relationships with students and colleagues, and carving out a space to grow and teach and learn, the stakes felt astronomical. But if I wanted my students to go all in, to try new things, not just now but in the future, I had to show - not just tell - them that it is okay to take big risks and to let them see me be vulnerable and uncomfortable in my vulnerability too. |

In order for this project to meet its objectives, in other words, my students and I had to be willing to accept the discomfort of trying something potentially terrifyingly new. Further, given that we all were embarking on new territory in some way or another, how would we know whether we achieved success?

Instinct. Observation. Reflection. Each is a valuable, though typically informal, method of assessing thinking and learning. Though multimodal artifacts like those students produced in the ADAPTING HAMLET project are notorious for posing challenges to standard methods of assessment because they aren't consistent in form, scope, medium, etc., students and I relied on a version of our MULTIMODAL COMPOSITION RUBRIC adapted to this project's objectives to formally measure their achievement of project objectives.

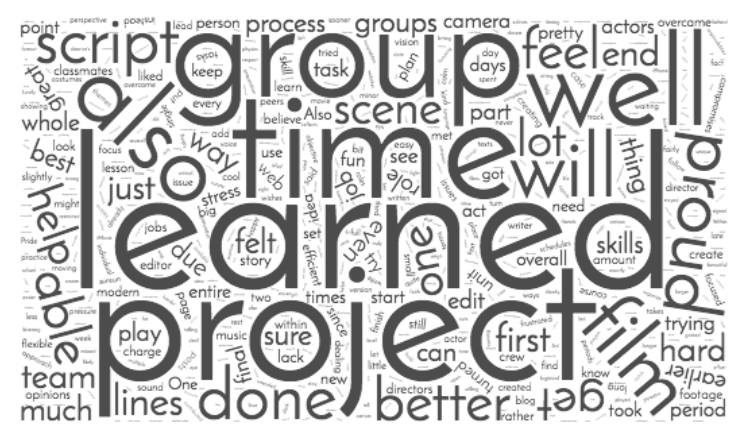

While rubrics can be very useful to the composing and assessment process, in order for students and I to see the fullest picture of the thinking and learning that grew out of this project, students composed, collected, and shared reflective writing and process pieces throughout their work on ADAPTING HAMLET. Students also completed self- and peer-evaluations. The word cloud and the block quotes on these two pages were drawn from these assessments. Additional student reflection can be found here.

Considered alongside the extensive contextualizing and reflective components of each class's website - including written reflections, interviews, and rejected takes - we can see the successful learning and growth behind even imperfect products. The learning remains visible, and for me, that learning is key. When these assessment vehicles are coupled with deliberate reflective writing and visible process work, even if the final product is not an exemplar of its medium, we can plainly see the DISCOVERY, the vital, vibrant learning that has happened.

Instinct. Observation. Reflection. Each is a valuable, though typically informal, method of assessing thinking and learning. Though multimodal artifacts like those students produced in the ADAPTING HAMLET project are notorious for posing challenges to standard methods of assessment because they aren't consistent in form, scope, medium, etc., students and I relied on a version of our MULTIMODAL COMPOSITION RUBRIC adapted to this project's objectives to formally measure their achievement of project objectives.

While rubrics can be very useful to the composing and assessment process, in order for students and I to see the fullest picture of the thinking and learning that grew out of this project, students composed, collected, and shared reflective writing and process pieces throughout their work on ADAPTING HAMLET. Students also completed self- and peer-evaluations. The word cloud and the block quotes on these two pages were drawn from these assessments. Additional student reflection can be found here.

Considered alongside the extensive contextualizing and reflective components of each class's website - including written reflections, interviews, and rejected takes - we can see the successful learning and growth behind even imperfect products. The learning remains visible, and for me, that learning is key. When these assessment vehicles are coupled with deliberate reflective writing and visible process work, even if the final product is not an exemplar of its medium, we can plainly see the DISCOVERY, the vital, vibrant learning that has happened.