The Parson

A parson is a priest of a small independent church. In the Canterbury Tales, the Parson is described by Chaucer as poor, but intelligent, faithful, and actually a genuine good person.

Commonplace Book

The Reasoning Behind Our Decisions

The Parson was a surprisingly fascinating pilgrim in the Canterbury tales. He may not have seemed that special at first, but, when analyzing his description, one can see that he was one of the few pilgrims that Chaucer actually respected. The foundation for Chaucer’s respect became clearer as the General Prologue went on. The Parson was honest, generous, and truly devoted to his parishioners. Each line of the story helped paint a picture of him. For this project, we examined Chaucer’s text and attempted to recreate this character portrait, and then we used it to aid us in choosing a fitting way to portray the Parson.

There are numerous pieces of the text that support the idea that the Parson was a genuinely good person. A rather recognizable example would be how Chaucer described the Parson as being “poore […] but riche […] of holy thought and werk”(Norton 205, 480-481). This emphasized that Chaucer viewed him as a faithful and loyal member of the clergy. This also brings up the important point that the Parson was not wealthy, at least not in terms of monetary wealth. This was an extreme contrast to the other pilgrims whose occupations were based in religion, such as the Monk. This particular man was described as having “sleeves purfiled at the hand [w]ith gris, and that the fineste of a land”(Norton 198, 193-194). He was obviously very wealthy, and the high quality fur that was lining his sleeves proved this. The contrast between the description of the Parson and the description of the other pilgrims with religion-based occupations serves to bolster the inference that Chaucer admired the Parson and viewed him as a respectable and honest man. This inference is further supported by how the Parson is very devoted to his parishioners. This is proven when Chaucer stated that “wid was his parissh, and houses fer asunder, but he ne lafte nought for rain ne thunder, […] to visite the ferreste in his parissh”(Norton 205, 492-496). The parson’s parishioners lived very far apart. He, however, did not let this deter him. Neither thunder nor rain could prevent him from visiting any one of his parishioners during a time of need. All in all, the Parson was, in all senses of the word, a good person, and this was the major guiding factor when we made our decisions about how to present his autobiography and the commonplace book.

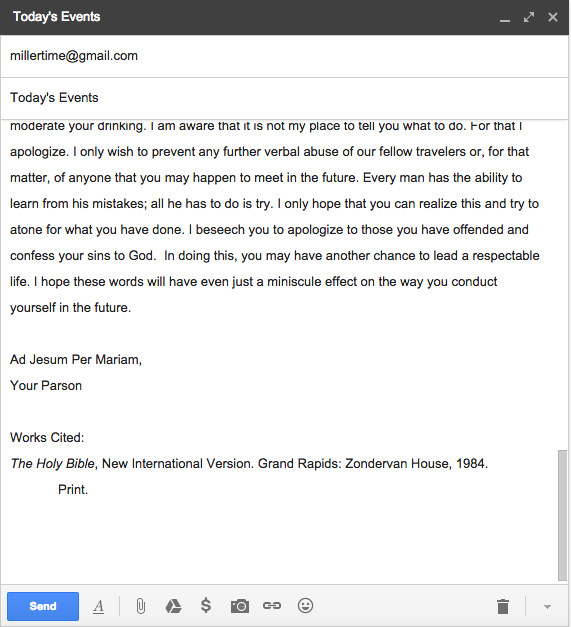

There were many factors that influenced our decision of the media through which to present the Parson’s reaction to the Miller’s tale. The parson was a very devoted and religious man. From this, we concluded that he would not favor the drama and disparagement that commonly occurs on most forms of social media. He would still, however, wish to make his opinions about the Miller’s tale known. The tale contained an excess of vulgar content and blatantly attacked the reputations of the Carpenter, Scholar, and Wife of Bath who were all members of this journey to Canterbury. Even worse, the Miller was intoxicated. This was proven when he outright admitted to the entire group that “[he was] dronke” (Norton 215, 30). The Parson, being the moral, faithful man that he was, would have been rather aggravated by the actions of the Miller and the contents of his tale. He is even described as being “to sinful men nought despitous”(Norton 206, 518). This means that he greatly disliked people who were sinful. Because of this, we concluded that he would most definitely make a move to reprimand the Miller for his actions. We decided, however, that he would make this move in a discreet way, so as to not publicly shame the Miller for his actions. His speech was not “daungerous ne digne,” and his teachings were “discreet and benigne”(Norton 206, 519-520). This meant that he was at heart a gentle person, and he wished to educate people in a way that was not hostile. He believed that this was more effective than a combative approach. After considering this more in depth profile of the Parson, we decided that the best way to express his discontent with the Miller’s tale would be through a strongly worded email.

Based on what we knew about the Parson, using an email to express his concerns just made sense. With an email, the Parson would be able to clearly express his discontent with the Miller’s actions and fully reprimand him, but still be able to avoid a public confrontation that could cause the offending pilgrim unnecessary embarrassment. An email would be able to meet both of the philosophies of the Parson’s: to reprimand those who have engaged in sinful behaviors, and to express his disappointment in a way that was neither combative nor humiliating. There was also another significant advantage to sending an email. If the Miller’s distasteful behavior continued even after receiving the first one, the Parson would be able to send a follow-up email or, if necessary, multiple follow-up emails. He was “in adversitee ful pacient,” which meant that he would be able to be persistent and patient in his movement to reform the Miller(Norton 205, 486). One final justification for our choice is that the Parson could tend to be long-winded and was not a very concise writer. This is proven by the fact that his tale is over one thousand lines long and is also rather tedious. The entire tale is about penance and the faults of humanity. An email would fit this type of writing very well because it can be as long as the writer desires. This aspect is perfect for the Parson, who would most definitely take advantage of that fact. This, along with all of the other points that were previously mentioned, all aid in justifying our decision to express the Parson’s reaction through email.

As we continued to determine the Parson’s persona in social media, we tried to find an internet niche that he might identify with when concerned with creating an autobiography. We also needed an audience that he would present such an autobiography to (as he would never post such a personal thing out of vanity). We concluded that there were two important factors that needed to be represented: his preaching/love of god, and a medium that could reach his audience (which we decided were his parishioners, who lived far from the parish). It was logical then, to make him a YouTube vlogger. The ranting and similar videos of a vlogger, would be very similar to a sermon, as both are a form of preaching their preacher’s beliefs. His parishioners would be his subscribers. We made the medium a “Draw My Life” video, which allows for an intuitive and engaging form of autobiographical storytelling (which the Parson would use to engage his parishioners). When making the video, we purposefully made the choice to keep drawings from being amazingly neat, to not use accents, and to keep a speaking voice that was relatively modern, as we wanted to sell the point of him being a modern-day vlogger, rather than just a medieval citizen who stumbled upon technology. Not much at all is given about the Parson’s life, so we decided to be more liberal in the storytelling, and try to show his personality more. We made a point of ensuring his speech was very God-fearing in nature (to a point) and that he practically publicized his honest and truthful character. In addition, we decided to not include the Parson’s brother the Plowman. This was a very controversial decision, as it was largely made due to time constraints, however we decided that the Parson would not focus much at all on his brother, who was already very religious, instead choosing to highlight his own struggles in finding holiness, as that would prove a greater lesson to his pupils.

Chaucer’s depiction of the Parson provided us with all the information we needed in order to successfully mimic the pilgrim’s demeanor. We tied together each quality that the Parson possessed with our own depiction of him. His genuine care for others led us to choose to express his reaction to the Miller’s tale as an email. His spread out parishioners inspired us to create a draw-my-life for his autobiography. Each choice we made was deliberate and justified by textual evidence.

The Parson was a surprisingly fascinating pilgrim in the Canterbury tales. He may not have seemed that special at first, but, when analyzing his description, one can see that he was one of the few pilgrims that Chaucer actually respected. The foundation for Chaucer’s respect became clearer as the General Prologue went on. The Parson was honest, generous, and truly devoted to his parishioners. Each line of the story helped paint a picture of him. For this project, we examined Chaucer’s text and attempted to recreate this character portrait, and then we used it to aid us in choosing a fitting way to portray the Parson.

There are numerous pieces of the text that support the idea that the Parson was a genuinely good person. A rather recognizable example would be how Chaucer described the Parson as being “poore […] but riche […] of holy thought and werk”(Norton 205, 480-481). This emphasized that Chaucer viewed him as a faithful and loyal member of the clergy. This also brings up the important point that the Parson was not wealthy, at least not in terms of monetary wealth. This was an extreme contrast to the other pilgrims whose occupations were based in religion, such as the Monk. This particular man was described as having “sleeves purfiled at the hand [w]ith gris, and that the fineste of a land”(Norton 198, 193-194). He was obviously very wealthy, and the high quality fur that was lining his sleeves proved this. The contrast between the description of the Parson and the description of the other pilgrims with religion-based occupations serves to bolster the inference that Chaucer admired the Parson and viewed him as a respectable and honest man. This inference is further supported by how the Parson is very devoted to his parishioners. This is proven when Chaucer stated that “wid was his parissh, and houses fer asunder, but he ne lafte nought for rain ne thunder, […] to visite the ferreste in his parissh”(Norton 205, 492-496). The parson’s parishioners lived very far apart. He, however, did not let this deter him. Neither thunder nor rain could prevent him from visiting any one of his parishioners during a time of need. All in all, the Parson was, in all senses of the word, a good person, and this was the major guiding factor when we made our decisions about how to present his autobiography and the commonplace book.

There were many factors that influenced our decision of the media through which to present the Parson’s reaction to the Miller’s tale. The parson was a very devoted and religious man. From this, we concluded that he would not favor the drama and disparagement that commonly occurs on most forms of social media. He would still, however, wish to make his opinions about the Miller’s tale known. The tale contained an excess of vulgar content and blatantly attacked the reputations of the Carpenter, Scholar, and Wife of Bath who were all members of this journey to Canterbury. Even worse, the Miller was intoxicated. This was proven when he outright admitted to the entire group that “[he was] dronke” (Norton 215, 30). The Parson, being the moral, faithful man that he was, would have been rather aggravated by the actions of the Miller and the contents of his tale. He is even described as being “to sinful men nought despitous”(Norton 206, 518). This means that he greatly disliked people who were sinful. Because of this, we concluded that he would most definitely make a move to reprimand the Miller for his actions. We decided, however, that he would make this move in a discreet way, so as to not publicly shame the Miller for his actions. His speech was not “daungerous ne digne,” and his teachings were “discreet and benigne”(Norton 206, 519-520). This meant that he was at heart a gentle person, and he wished to educate people in a way that was not hostile. He believed that this was more effective than a combative approach. After considering this more in depth profile of the Parson, we decided that the best way to express his discontent with the Miller’s tale would be through a strongly worded email.

Based on what we knew about the Parson, using an email to express his concerns just made sense. With an email, the Parson would be able to clearly express his discontent with the Miller’s actions and fully reprimand him, but still be able to avoid a public confrontation that could cause the offending pilgrim unnecessary embarrassment. An email would be able to meet both of the philosophies of the Parson’s: to reprimand those who have engaged in sinful behaviors, and to express his disappointment in a way that was neither combative nor humiliating. There was also another significant advantage to sending an email. If the Miller’s distasteful behavior continued even after receiving the first one, the Parson would be able to send a follow-up email or, if necessary, multiple follow-up emails. He was “in adversitee ful pacient,” which meant that he would be able to be persistent and patient in his movement to reform the Miller(Norton 205, 486). One final justification for our choice is that the Parson could tend to be long-winded and was not a very concise writer. This is proven by the fact that his tale is over one thousand lines long and is also rather tedious. The entire tale is about penance and the faults of humanity. An email would fit this type of writing very well because it can be as long as the writer desires. This aspect is perfect for the Parson, who would most definitely take advantage of that fact. This, along with all of the other points that were previously mentioned, all aid in justifying our decision to express the Parson’s reaction through email.

As we continued to determine the Parson’s persona in social media, we tried to find an internet niche that he might identify with when concerned with creating an autobiography. We also needed an audience that he would present such an autobiography to (as he would never post such a personal thing out of vanity). We concluded that there were two important factors that needed to be represented: his preaching/love of god, and a medium that could reach his audience (which we decided were his parishioners, who lived far from the parish). It was logical then, to make him a YouTube vlogger. The ranting and similar videos of a vlogger, would be very similar to a sermon, as both are a form of preaching their preacher’s beliefs. His parishioners would be his subscribers. We made the medium a “Draw My Life” video, which allows for an intuitive and engaging form of autobiographical storytelling (which the Parson would use to engage his parishioners). When making the video, we purposefully made the choice to keep drawings from being amazingly neat, to not use accents, and to keep a speaking voice that was relatively modern, as we wanted to sell the point of him being a modern-day vlogger, rather than just a medieval citizen who stumbled upon technology. Not much at all is given about the Parson’s life, so we decided to be more liberal in the storytelling, and try to show his personality more. We made a point of ensuring his speech was very God-fearing in nature (to a point) and that he practically publicized his honest and truthful character. In addition, we decided to not include the Parson’s brother the Plowman. This was a very controversial decision, as it was largely made due to time constraints, however we decided that the Parson would not focus much at all on his brother, who was already very religious, instead choosing to highlight his own struggles in finding holiness, as that would prove a greater lesson to his pupils.

Chaucer’s depiction of the Parson provided us with all the information we needed in order to successfully mimic the pilgrim’s demeanor. We tied together each quality that the Parson possessed with our own depiction of him. His genuine care for others led us to choose to express his reaction to the Miller’s tale as an email. His spread out parishioners inspired us to create a draw-my-life for his autobiography. Each choice we made was deliberate and justified by textual evidence.